Editor’s Note: This interview with Claire Sullivan took place before the 2023 Hawai‘i wildfires. Farm Link Hawai‘i has been working with Maui and Hawai‘i Island producers whose businesses were affected to help them make up for lost markets.

Omidyar Fellow Claire Sullivan grew up with strong values around food. She was taught to appreciate the many resources it takes—from land and water, to the people that grow, produce, and prepare food—to get it from farms, to stores, and finally, to your plate.

“My mom and my aunty worked at Kokua Market in the seventies,” she says. Buying fresh produce and local products at the co-op was part of their family’s history and set of practices.

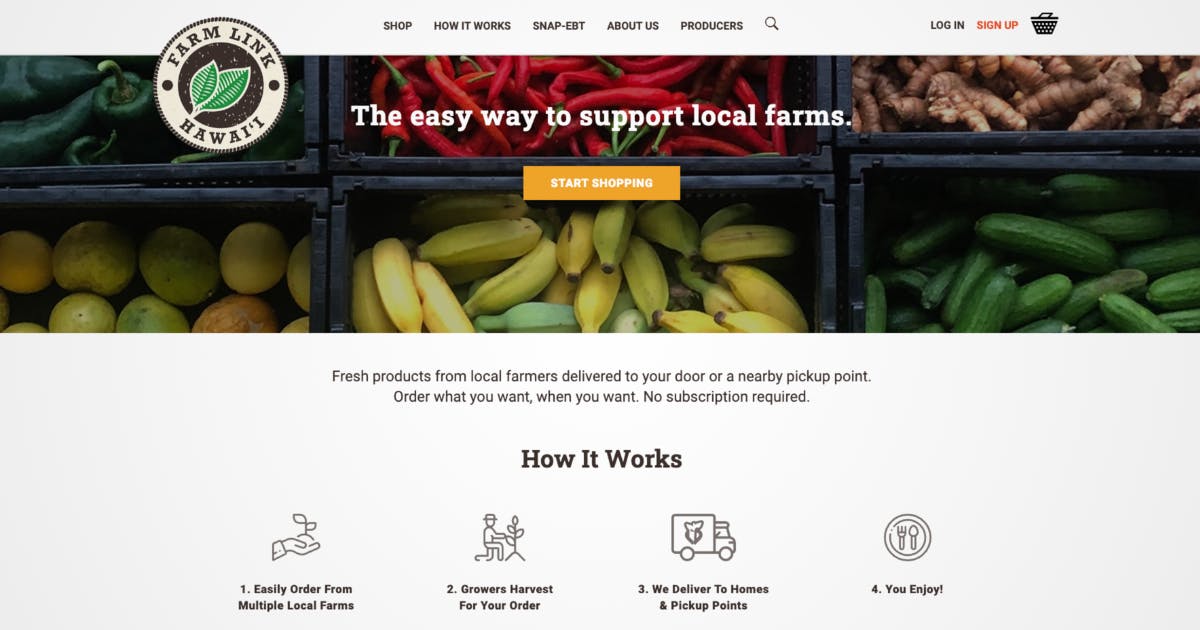

Today, Claire is CEO of Farm Link Hawai‘i, an online marketplace that connects Hawai‘i-based growers with buyers across O‘ahu, providing direct-to-door delivery of locally sourced groceries. For more than twenty years, she’s found fresh, innovative ways to improve Hawai‘i’s food systems and give families equitable access to healthy food.

“It’s marrying up the supply side work with equitable access, and to me, that’s what’s so radical about the work at Farm Link Hawai‘i.”

NUTURING A CAREER IN AGRICULTURE

Claire began her career with Maui Land & Pineapple (ML&P), at a time she says was “an exciting moment of imagining what a post-plantation future might look like.” She also personally grappled with the plantation legacy and the lasting consequences of devoting so many resources into the production of sugar and pineapple.

“It’s what propelled me into food systems work as my career.”

After leaving ML&P, she went to graduate school, where she focused on the evolution of organic as a radical movement to a regulatory regime. When it was time to return home in 2007, she was faced with an interesting decision.

She remembers asking herself, “How could I be a constructive participant in the food system [in Hawai‘i]? On the one hand, I should just go work at Kokua Market, right? That’s values aligned and doing important work.”

However, she was also aware of a new player about to enter the Hawai‘i market: Whole Foods.

“They had this huge purchasing checkbook that was new money coming to town,” she says. “And that checkbook was either going to be oriented towards California and [Whole Foods’] existing supply chain, or as much of it as possible could be redirected to producers here.”

To Claire, the choice for greater impact was clear, and in 2008, she became the first Hawai‘i team member at Whole Foods—before its first store in Kāhala even opened. She played a pivotal role in their Hawai‘i operations, building a local purchasing program that at the time worked with over 300 local producers and purchased more than $12 million annually in local products.

“Many of us eat multiple times a day. We’re very fortunate that we get to do that. There’s also some obligation that comes along with that fortune of having access to good food resources.”

The market’s presence quickly had an influence on other retailers who wanted to emulate the success of the program. It also improved the relationships between grocers and producers. But following a decade at Whole Foods, Claire thought she might be ready for a career change.

“I was honestly just feeling so burnt out,” she admits of her departure. “I was feeling pretty cynical because the challenges were so significant. But I took a little bit of a break and realized I wasn’t done with Hawai‘i food and agriculture.”

She reached out to talk story with her friend and mentor Gary Maunakea-Forth at MA‘O Organic Farms. That conversation soon turned into an opportunity to join the MA‘O Farms team.

“You couldn’t ask for a more rooted and meaningful way to get back into food system work.”

At MA‘O, Claire assisted with the expansion of their operations, growing from 20 to nearly 300 acres and supporting the capital campaign that funded the expansion.

“It was the first time since I’d been at ML&P that I was back on the producer side,” she recalls. “But once again, I was seeing that there was not a buyer here who was meeting producers with making commitments, was being innovative, and was willing to share in the risks.”

“It’s the producers who put the stuff in the ground,” she explains, “and if it doesn’t come to fruition, they don’t see a penny, while the buyer just waits until it shows up at the back door and gets to share in the profits. It’s a very unequal risk distribution and the margins are thinnest on the producer side.”

Navigating these challenges helped her realize how her career had led her to this point. “It was a really big part of the motivation to say I have this skillset that’s relevant on the buy side and that’s where we’re missing partners.”

CONNECTING THE LINKS

Claire points out that in Hawai‘i’s food system, demand for local product is “pretty voracious,” and for several decades, the demand has outstripped supply.

“It’s easy to think that we should tell producers to grow more and make more,” she says. “But there are so many systemic barriers that they are facing, whether that’s access to land or the cost of ingredients or amendments. It’s not realistic to put all that expectation on the producer.”

While there were some buyers including food hubs and local chefs who were addressing this imbalance, Claire says most efforts were limited in geography or scope.

“There was no one in the landscape who was playing that role in as robust a way as I thought could or should happen.”

Aiming to fill that need, Farm Link Hawai‘i was developed in 2015 by software developer turned organic farmer Rob Barreca.

“Rob and I knew each other through the food and ag space,” Claire says. “He created Farm Link Hawai‘i to support other small-scale producers like himself. At that point, it was really a business-to-business effort, largely serving restaurants and other wholesale accounts.” However, Rob always aspired that Farm Link Hawai‘i could eventually provide direct-to-consumer service.

“Last-mile delivery is the hardest business to be in,” she says. “Why on earth would anyone want to tackle that?”

Then, the COVID pandemic happened.

“Thank goodness Rob had been working on it in part as a participant in Elemental Excelerator,” she says. “And through that work, in two weeks, he just did it. And it meant that all those producers [that worked with Farm Link Hawai‘i] never lost market share.” This novel pipeline to consumers was critical in the early pandemic days.

“The relationships with other [Omidyar] Fellows who are doing work in adjacent spaces is both emotionally and cognitively nourishing, and organizationally vital.”

“All of that work was done before I came on board,” she shared, “and I really honor and respect the effort Rob put into that.”

Claire, then still at MA‘O, and Rob had monthly calls to share their learnings as they maneuvered with their organizations’ operations through the pandemic.

“Over these conversations, it organically emerged that we should be doing something together,” she says. “There was so much resonance of values, interest, and understanding of what an activist buyer could do in the system.”

She also recognized an opportunity to align her experience with supply building in partnership with producers, while also broadening access to good, local food for the whole community.

Everything—COVID, their conversations, and realizing this opportunity—converged while Claire was in the curriculum phase of the Omidyar Fellows program, right before she would go on her Individual Learning Excursion (ILE).

“There I was, headed off to my ILE, making this huge life and career decision, also wondering how family and a baby fit into this whole equation,” she recalls.

“[It became] quite clear during my ILE that I wanted to join Farm Link Hawai‘i and I was finally ready to start a family,” she says, and in the same week in 2001, she became Farm Link Hawai‘i’s CEO and started the journey to become a new mom.

“It was not exactly the perfect timing, but you’re not exactly in charge of one of those two things,” she laughs.

The Farm Link Hawai‘i Team

Photo courtesy Ashley Lukens Consulting

GROWING ACCESS THROUGH INNOVATION

Direct home delivery continues to contribute to Farm Link Hawai‘i’s success. And with Claire on the team, Rob has shifted roles onto the technology side as Farm Link Hawai‘i’s chief technology officer.

“It was really a chance to marry up his skillsets on technology in service of food, ag, and equitable access,” Claire elaborates. “Rob’s efforts are what took us from offering our SNAP/EBT (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program / Hawai‘i Electronic Benefit Transfer) as a transaction at a [fixed] hub pickup location… to the point where we could do SNAP/EBT [transactions] with home deliveries.”

Combined with Hawai‘i’s DA BUX Double Up Food Bucks program that provides a 50% off discount on local produce, Farm Link Hawai‘i’s home delivery makes it more convenient for SNAP/EBT customers to get fresh food that might not be available in their neighborhood market. They’re even working on a way to accept SNAP transactions online, just like credit cards.

“We really make the food as affordable as possible and deliver with no fee to anybody using SNAP,” she says. “It’s marrying up the supply side work with equitable access, and to me, that’s what’s so radical about the work at Farm Link Hawai‘i.”

While Rob focuses on technological innovations, Claire has been engaged with Farm Link Hawai‘i’s supply chain development, operations, and cultivating partnerships.

Farm Link Hawai‘i has partnered with Wai‘anae Coast Comprehensive Health Center and Waimānalo Health on their produce prescription programs and other preventative health measures, such as Waimānalo Health Center’s diabetes prevention project.

“It’s a very explicit acknowledgement that food is medicine and ensures that folks who are using those prescriptions have access to the best local produce.”

Claire is also proud that Farm Link Hawai‘i can deliver island wide, including to parts of O‘ahu where grocery options have traditionally been limited.

“We have these two ends of the spectrum [of customers we serve],” she says.

On one side, there are people with discretionary income who choose to spend their resources on quality food. Without Farm Link Hawai‘i, they might have to go to multiple stores and farmers markets to get the variety of items they want.

On the other side, there are SNAP EBT customers, which represent 20% of Farm Link Hawai‘i’s business. They face a different set of access challenges, like their proximity to stores and farmers markets, or how their schedules, multiple jobs, and lengthy commutes often conflict with store and market hours.

“All of these physical and socioeconomic barriers play out in different ways, but it means that our solution is really attractive to both ends of the spectrum,” she says. However, she also admits that “what we don’t do well is serve the middle—ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) families—who aren’t receiving federal benefits and don’t have that support, yet don’t have the discretionary income to afford buying local.”

“There is a really significant chunk of folks in our community who fall in this big middle gap,” she says, and recognizes there’s a lot more work to be done.

“I do appreciate that our model allows us to tackle both ends, and perhaps through our work, build up a more robust supply. We’re working towards a day when local food is more affordable to fill in the gap and meet those folks in the middle.”

MUTUALLY NOURISHING RELATIONSHIPS

In addition to developing partnerships, Claire credits her associations with other Omidyar Fellows as integral to her success and the success of Farm Link Hawai‘i.

“It’s existentially important,” she says. “The relationships with other Fellows who are doing work in adjacent spaces is both emotionally and cognitively nourishing, and organizationally vital.”

One collaboration she highlights is working with Fellow Keoni Lee and Hawai‘i Investment Ready.

“We were in the most recent HIR cohort, which was food system oriented,” she shared. “That work was transformative to us and so important to the evolution of our business approach, and very importantly, our capacity to seek out funding.”

The experience helped them articulate their financial returns and substantial socioeconomic and cultural returns to investors.

“The list of Fellows with whom we do work with is really extensive, and I’m deeply grateful for them.”

Families on O‘ahu can order fresh local products and get them delivered or pick them up from community pickup locations.

FEEDING A MOVEMENT

While Farm Link Hawai‘i makes advances towards making Hawai‘i more prosperous, healthy, and resilient, Claire says there’s an easy way for individuals to improve Hawai‘i’s food system: by making meaningful and intentional food choices.

“What are you going to eat today?” she asks. “What are the ramifications for your health, the health of the community, the environment, and the sociocultural fabric around you? Your food has those implications, whether you’re paying attention to them or not.”

She explains that these decisions have direct impacts on the food system, the people who are growing the food, and the community who lives where the food is grown.

“We’re all dealing with the climate change consequences of our dietary choices. The opportunity is to pay attention and not try to make it perfect overnight, but to recognize that each time you do make one of those more proactive decisions, that you’re choosing this food because it’s good for your body and all the other bodies, human and not human, around you.”

“There’s so much power in your choices about food,” she concludes, “and to me, this is why food and ag is the space I chose. It’s the nexus point for all our wellbeing: economic and ecological wellbeing, physical health, cultural heritage, and joy. It’s all wrapped up.”

To learn more about Farm Link Hawai‘i, visit farmlinkhawaii.com or @farmlinkhawaii on Instagram.

Chef Hui, led by co-founders Amanda Noguchi and Omidyar Fellow Mark Noguchi believe in the incredible strength of uniting in the wake of adversity.